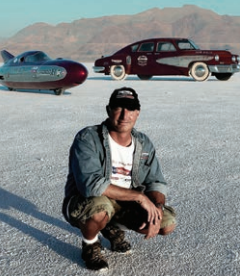

Story By: Steve Tremulis

Steve Tremulis is a biomedical engineer and an inventor with more than 50 patents. He is the nephew of Alex Tremulis, Preston Tucker’s Chief Stylist for the Tucker 48. Also he is curator of his uncle’s incredible archive of photos, drawings, speeches, and models spanning over a half century of automobile design. A long-time board member for Tucker Automobile Club of America, Steve now serves on the AACA Museum, Inc.’s Tucker Advisory Committee.

Table Of Contents

- A Real Designer

- Influence of the Masters

- Rear Engine Placement

- The War Years

- Enter Preston Tucker

- Tremulis Leads Prototype Design

- A Final Thought

- The Tucker ’48’s 75th Anniversary Celebration

The Tucker’s styling has sparked many opinions and descriptions throughout

the decades. There appears to be little room for indifference. Either you

love it or hate it. At its June 18, 1947 unveiling, one of the attending reporters

described what it was like to first see Preston Tucker’s car of tomorrow:

“In an expectant hush suitable to so historic an event, the curtains of an improvised platform parted, revealing to the accompaniment of pleased gasps a maroon teardrop creation so low and sweeping in its lines that one reporter wrote, ‘It looks as if it’s going 90 even while standing still.’ About as long as a Cadillac, it had a third, ‘Cyclops eye,’ headlight planted in the middle of the nose. The front bumper looked like the horns of a Texas steer, and the front fenders curved like the half-folded wings of a hovering bird.” As with most iconic designs, those fenders have a compelling story of their own.

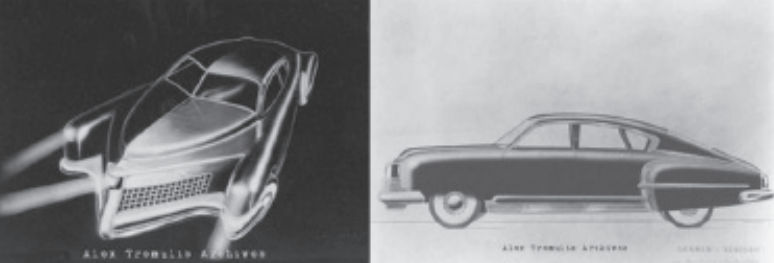

fenders. Photos: Alex Tremulis Archives

The drama surrounding the rise and fall of the Tucker Corporation and its impact on society has been told many times over in books and in film, but there’s a fascinating origin to those unique front fenders that dates back over a decade before their debut on the Tucker 48 that has yet to be told, until now.

Photo:Detroit Public Library Digital Collections

“A Real Designer”

Their origins can be traced back to a future Automotive Hall of Fame stylist still cutting his teeth in the styling world. Alex Tremulis pursued his passion for drawing cars by playing hooky from school, but unlike most kids with a day off, Tremulis spent his time at the dealerships for Stutz and Duesenberg, drawing the magnificent automobiles displayed in their Michigan Avenue showrooms on Chicago’s famed “Motor Row.” His talents were soon recognized by Donn Hogan, the sales manager at Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg. At the ultra-luxury dealership, you didn’t just buy a Duesenberg off the showroom floor, rather you would buy the Duesenberg chassis and a special coach builder would design and build the custom bodywork to your liking. Using Tremulis as the local illustrator, Hogan could bypass the time it would normally take to send a customer’s ideas to the Indianapolis-based headquarters for a drawing and have a sketch in the customer’s hands the very next day. Tremulis was paid $1.00 for a pencil sketch and $2.50 for a rendering in color. To the fledgling designer, even one dollar was a huge increase in pay over the 10 cents an hour he was paid for shoveling rotten fruit out of grocery vendors. With his first real paying job, he said “Now I am a designer” and never looked back.

Photo: Source unknown

Influence of the Masters

Within a couple of years, Tremulis eventually found steady work under the great Gordon Buehrig at Auburn, learning the ropes from the master. He proved to be a fast learner and a talented artist. So much so that when Buehrig left Auburn in 1936, Tremulis was promoted to Chief Stylist at the age of 22. Buehrig, however, wouldn’t be the only automobile designer to influence the young stylist. In his search for a more reliable income, Tremulis had found his way into the styling studios at Briggs Manufacturing in Detroit, where he was brought in under the tutelage of another noted designer, John Tjaarda. It would be his first of several stints at Briggs and LeBaron.

At the time, Briggs was best known for building the bodies for several car companies including Ford and Chrysler under the LeBaron nameplate. Edsel Ford often sought refuge in the design work at Briggs as it offered a welcome relief from the tight reigns Henry Ford kept on his son’s styling ideas. Luckily, Tjaarda tasked Tremulis with putting down on paper the styling discussions that Edsel Ford would have with Tjaarda’s staff. Tremulis recalled one discussion with Edsel Ford about the value of the horizontal beltline in creating the image of a longer, lower body design. Ford demonstrated the illusion by folding a sketch and illuminating it by candlelight at various angles, a moment that would leave an everlasting image in the psyche of Tremulis. It would be one of Tjaarda’s earlier designs for Ford, however, that would surely have as much an influence on Tremulis as any of Edsel Ford’s tricks of the trade. In the 1920s Tjaarda pursued a series of ultra-streamlined automobiles he called the Sterkenburgs, visually similar to the design of Hans Ledwinka’s Tatra. Tjaarda’s Sterkenburgs were also seen as aerodynamic as their rear-engine designs allowed for an overall teardrop shape to cheat the wind.

By 1933 he had refined the Sterkenburg into a prototype that was presented by Ford at the 1933-34 World’s Fair in Chicago. Dubbed “The Briggs Dream Car”, it could be considered as one of the very first concept cars shown to the public to judge viewer reactions. Ford liked what they both saw and heard and pursued the concept, although they felt it would be better accepted by the general public with the engine located up front under the Lincoln nameplate. The task of modifying the front end to accept the more conventional engine placement would go to the talented Bob Gregorie, but most of the design credit for the 1936 Lincoln Zephyr would rightly go to Tjaarda.

Tremulis later compared John Tjaarda to Preston Tucker as “a tireless proponent of the rear-engined automobile, whose enthusiasm for the principle reduced every other configuration to the status of a Napoleonic coach.” The advantages Tjaarda saw in a rear engine placement were not lost on Tremulis, and he quickly became a disciple.

Rear Engine Placement

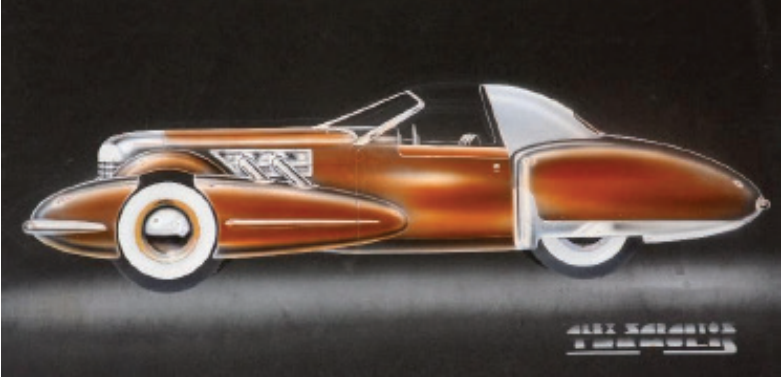

With the weight of the engine in the back over the drive wheels, traction and

stability would be greatly improved. No driveshaft running the length of the car

meant no hump running through the passenger compartment, leaving more room for travelers to stretch their legs. Engine noise and the mechanics of transferring power were located well behind the driver, resulting in a quieter ride. With these benefits in mind, in February of 1936, Tremulis drew up his own proposal for Briggs based on Tjaarda’s philosophy. His rendering of an aerodynamic bubble-topped, rear-engined concept was nothing short of spectacular. It would be this rendering that Tremulis would later reference while sketching out his ideas for Tucker’s winged fenders, but first the world would have to grapple with the looming international conflict destined to impact so many lives.

The War Years

World War II brought a temporary suspension of all automobile manufacturing

and a focus towards supporting the war effort. In February of 1942, General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, and all other car manufacturers mothballed their civilian automobile tooling in order to produce aircraft, tanks, jeeps, ships, and the millions of accessories needed to win a war.

It wasn’t until 1945 that the resumption of manufacturing cars for the general public would resume, albeit rather slowly. It would take until 1949 for production to equal its pre-war 1941 levels even though the pent-up demand for new cars was considerable. The tooling used to meet the consumers’ demand, however, was the same tooling that was placed in storage before the shutdown, meaning that your new car after the war was essentially identical to the car you had before the war. This left a tremendous opportunity for a new car manufacturer to create a new design without having to rely on old tooling to meet the demand created by the shutdown.

Enter Preston Tucker

Enter Preston Tucker with a futuristic “Car of Tomorrow” that grabbed the attention of every new car buyer. It wasn’t a hard sell: Would you rather buy a new car that still looked like that old broken-down car in your garage, or step into the future with a sleek, new design with novel features not found in most of its contemporaries? The new Tucker would indeed capture the imagination of an entire nation through both advertising and word of mouth. And it would be the new streamlined Tucker, with its rear-engine layout and “a series of spectacular engineering innovations”, that would prompt Alex Tremulis to schedule an appointment with Preston Tucker. Little did Tremulis know at the time, but Preston Tucker’s initial stylist for Tucker’s “Torpedo”, George Lawson, had left the company months earlier, leaving a void within the design department.

Indeed, Tucker was behind in showing progress on his new car. In September 1946, Preston Tucker had promised a prototype car by Christmas. In October, he again promised a prototype demonstrator would be ready by the first of the new year. So, when Tremulis met with Tucker in December, the timing was perfect to bring in his fresh ideas, and he wasted no time in creating the first prototype, the “Tin Goose”. But first, a new design had to be created, roughly based on images and a 1:4 scale model that Lawson had provided. As Alex Tremulis recalled, “One of the first problems I had to overcome was to convince Tucker that the movable front fenders had to go.” Time was of the essence and the engineering difficulties in sorting out Lawson’s cycle fenders did not support Preston Tucker’s desire to have a prototype built within 60 days. So Tremulis re-designed the car with conventional fixed fenders and made the center headlight turn with the wheels instead of the movable fenders. Tremulis’ elegantly simple solution retained the safety factor of being able to see where you’re turning, yet significantly shortened the timeline to completion of the first prototype.

Tremulis Leads To Prototype Design

Along with the deletion of the steerable fenders, he also eliminated the flowing

pontoons from his first initial series of drawings as he felt they were already

dated. Preston Tucker, however, liked the first fenders and felt first impressions

were usually correct, so the unique pontoons stayed. A great decision, as these characteristic fenders would forever be identified with Tucker cars. With these

design changes also came a new name: The Tucker 48. Gone was the Torpedo

name as it was decided that the explosive reference was too reminiscent of the

horrors of the war just ended.

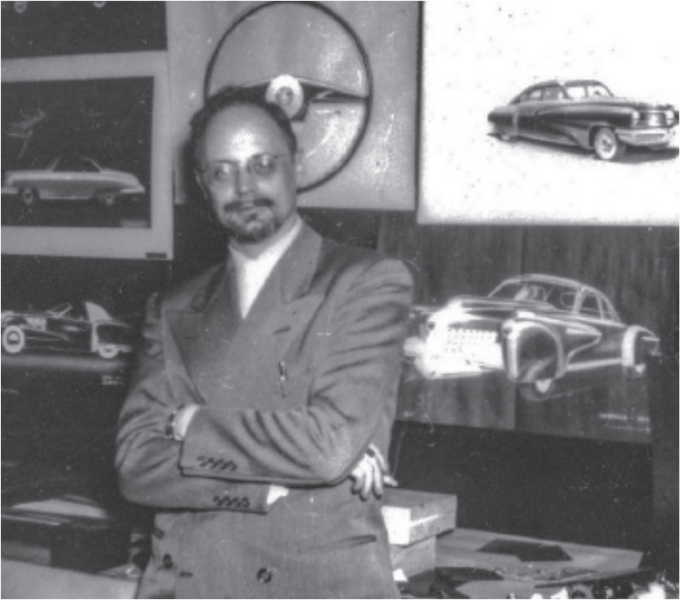

That brings us back to those unique “half-folded wing” fenders where a glimpse into Tremulis’ design studio completes the story. A vintage photo of Tremulis in the Tucker automotive styling studio shows a wall of renderings that not only illustrate new Tucker concepts but also include a few drawings from Tremulis’ past. One such drawing, in particular, harkens back to his days at Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg. He had conceptualized what he thought would have been a natural progression for the supercharged line of Cord automobiles had the company survived.

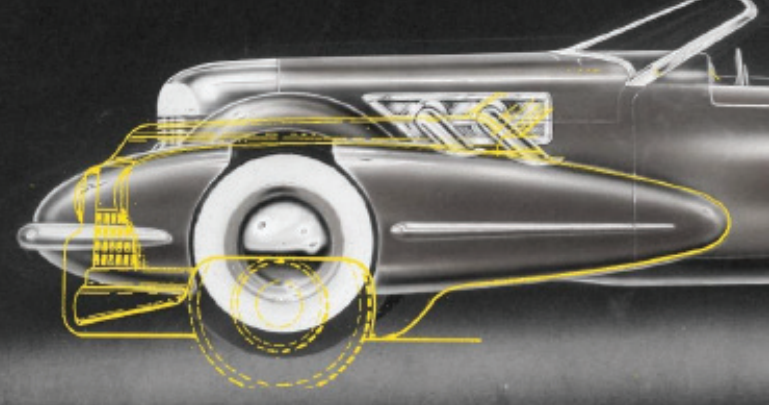

The beautiful rendering not only includes Tremulis’ original contributions to the supercharged Cord 812 with the external exhausts but also includes a sweeping pontoon front fender much lower in profile and more streamlined than on the original Cord. But a loser look reveals significant insight into the mind of the stylist: When compared to the March 1947 illustration used for the Tucker patent application, the fender has precisely the same contour and dimensions as those on the Tucker 48. Throughout the following months of development, the curves were slightly refined, but the basic shape from the Cord remained.

The unique Tucker fenders, so readily identified with the “Car of Tomorrow”, ended up being inspired by the Briggs bubble top and, for all practical purposes, came straight off a supercharged Cord.

A Final Thought

And that completes the story of how the winged fenders came to be. But, as with all “new” designs, the development of each of the other notable features of the Tucker also tells similar stories of how they came about. As the master portrait artist from the 18th century, Sir Joshua Reynolds, so astutely noted: “Invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited

in the memory. Nothing can be made of nothing; he who has laid up no materials can produce no combinations.”

Celebrate The Tucker ’48’s 75th Anniversary With The AACA Museum

This story was brought to you by our Winter 2022 edition of Reflections. To find more stories like this check out our Auto Collection Best Reads. We’re proud to showcase Tucker Automobiles as one of our Permanent exhibits, The Cammack Tucker Collection, showcasing famous models #1001, #1022, and #1026 along with factory test chassis and general prototypes.

This summer, from June 16th-June 18th you can join the AACA Museum in celebrating Tucker ’48’s 75th Anniversary. This event will celebrate the legacy of Preston Tucker as his “Car of Tomorrow” lives on today. We’ll be joined by Tucker family members, Tucker owners, and relatives of those who played significant roles in developing the Tucker ’48. It also brings together Tucker enthusiasts, motoring experts, and historians as we celebrate all things, Tucker. Head on over to our event page to learn more, reserve your tickets, and get resources for hotel accommodations for out-of-town guests.